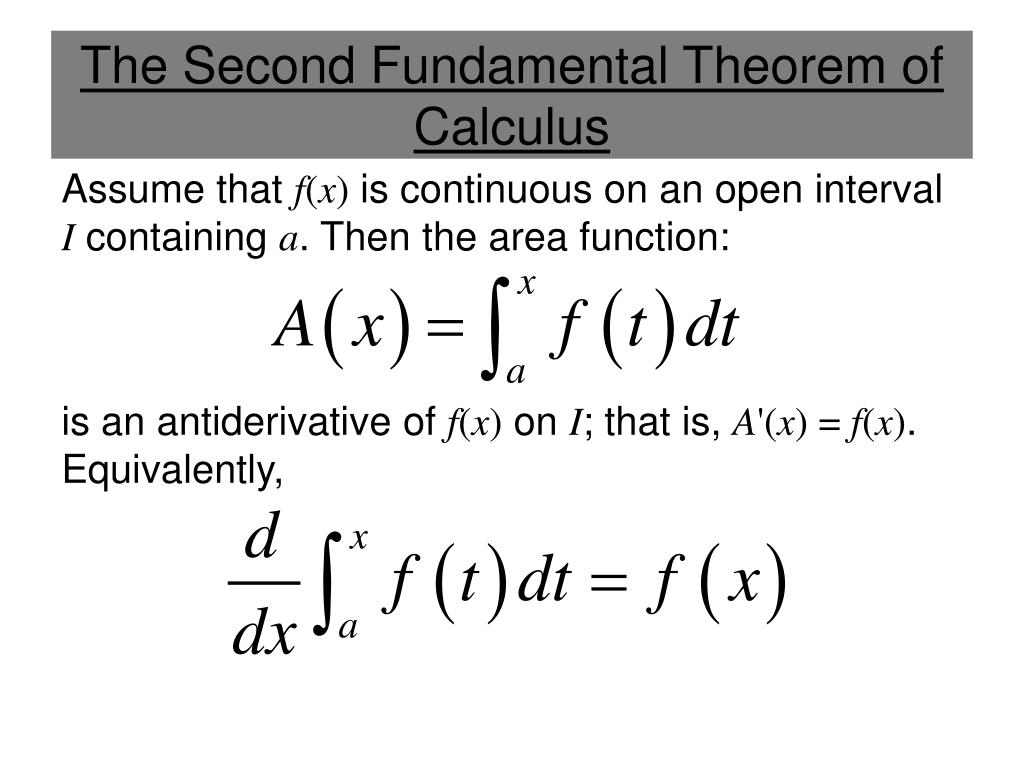

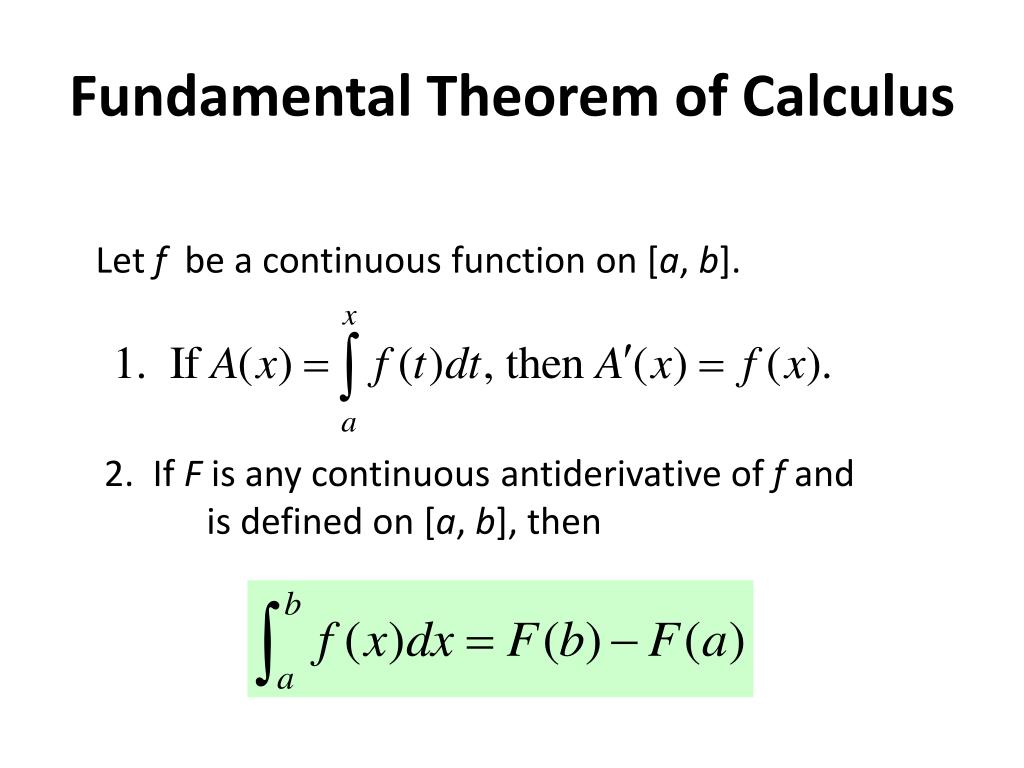

The qversion of this theorem was stated in 5 as follows. Specifically, if a continuous function F( x) admits a derivative f( x) at all but countably many points, then f( x) is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable and F( b) − F( a) is equal to the integral of f on. If f is a continuous function on an interval (a b), then f has an antiderivative on (a b). The conditions of this theorem may again be relaxed by considering the integrals involved as Henstock–Kurzweil integrals. Conversely, if f is any integrable function, then F as given in the first formula will be absolutely continuous with F′ = f almost everywhere. However, if F is absolutely continuous, it admits a derivative F′( x) at almost every point x, and moreover F′ is integrable, with F( b) − F( a) equal to the integral of F′ on. This result may fail for continuous functions F that admit a derivative f( x) at almost every point x, as the example of the Cantor function shows. Given a continuous function y = f( x) whose graph is plotted as a curve, one defines a corresponding "area function" x ↦ A ( x ) The first fundamental theorem may be interpreted as follows. These two values are approximately equal, particularly for small h. Alternatively, if the function A( x) were known, this area would be exactly A( x + h) − A( x). Geometric meaning The area shaded in red stripes is close to h times f( x). Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) systematized the knowledge into a calculus for infinitesimal quantities and introduced the notation used today. Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) proved a more generalized version of the theorem, while his student Isaac Newton (1642–1727) completed the development of the surrounding mathematical theory. The first published statement and proof of a rudimentary form of the fundamental theorem, strongly geometric in character, was by James Gregory (1638–1675). The historical relevance of the fundamental theorem of calculus is not the ability to calculate these operations, but the realization that the two seemingly distinct operations (calculation of geometric areas, and calculation of gradients) are actually closely related.įrom the conjecture and the proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus, calculus as a unified theory of integration and differentiation is started. The origins of differentiation likewise predate the fundamental theorem of calculus by hundreds of years for example, in the fourteenth century the notions of continuity of functions and motion were studied by the Oxford Calculators and other scholars.

Fundamental theorem of calculus formula how to#

Ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to compute area via infinitesimals, an operation that we would now call integration. Before the discovery of this theorem, it was not recognized that these two operations were related. The fundamental theorem of calculus relates differentiation and integration, showing that these two operations are essentially inverses of one another.

This greatly simplifies the calculation of a definite integral provided an antiderivative can be found by symbolic integration, thus avoiding numerical integration.

Ĭonversely, the second part of the theorem, the second fundamental theorem of calculus, states that the integral of a function f over a fixed interval is equal to the change of any antiderivative F between the ends of the interval. This implies the existence of antiderivatives for continuous functions. The first part of the theorem, the first fundamental theorem of calculus, states that for a function f, an antiderivative or indefinite integral F may be obtained as the integral of f over an interval with a variable upper bound. The two operations are inverses of each other apart from a constant value which depends on where one starts to compute area. The fundamental theorem of calculus is a theorem that links the concept of differentiating a function (calculating its slopes, or rate of change at each time) with the concept of integrating a function (calculating the area under its graph, or the cumulative effect of small contributions).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)